Kehailan just stood there, looking at the empty spot in the docking ring and shaking his head. “Of course you know without any shadow of a doubt who took it,” he said irritably.

“Did I say that?” the man in the adjutant’s uniform asked, his eyes, his voice, his attitude all proclaiming his contempt for Kee’s defense of his father. “All I said was, the only fugitive we have who is intelligent enough to fly a prototype clipper is Ardenai Firstlord.”

Kehailan’s ears were pinned tight with annoyance, and he kept swallowing, trying to control the anger rising in his throat when he tried to speak. “And I said, in that case no crime has been committed, because the clipper belongs to Ardenai in the first place. He designed it. It’s his personal craft. It was brought here by his personal physician and left for minor adjustments to the navigational system while Pythos went on with constituents to a conference on SeGAS-4. The conference is over by now. How do you know Pythos did not return to take the clipper back to Equus?”

The adjutant ignored him, and he could feel himself beginning to tremble. First the hands, then the legs. His muscles were tensing with the need to strangle the man when a large hand with formidable claws attached itself to his forearm. “Don’t give him the satisfaction,” Bonfire hissed. “Stay cool. Leave this little one to me.”

The adjutant smirked. “No need to be defensive, Commander. Surely you do not think we would hold your sire’s crimes against you?”

“What crimes?” Kehailan asked calmly, only his ramrod straight back and pinned ears betraying the anger he felt. The shaking had stopped. “So far there are only questions to be asked. How terrible a crime can it be for a man to take his own vessel?”

“Criminals do not own property, Wing Commander.”

“You, to your possible detriment, are forgetting that the Thirteenth Dragonhorse is above the law. Any law. He IS the law,” Kehailan remarked, walking toward the docking ring’s personnel exit. “Too, I find it interesting that the man entrusted to keep law and order on this base has no concept of due process, which makes me question your credentials. And, by the way, when was Adjutant De Los Angeles replaced, and on whose order? Never mind answering that. I shall check for myself.” The door hissed open and he was gone.

“He doesn’t like you much,” Bonfire Dannis smiled, “but I could. You look very tasty to me. I don’t care that you and your security squad are imposters.” The man in the uniform looked startled, and it made her laugh. “Silly boy, the commander’s a telepath, and you’re sending on all frequencies. He knows you’re pretending to be Adjutant while the real one is on holiday. Still, I do think there’s time for just a quickie before they come and take you away.”

Kehailan heard Bonfire’s sharp bark of laughter, and smiled to himself as the adjutant blew by at a gallop. He knew her sense of humor. A very gentle woman, actually, but frightening in size and aspect … and the perpetually hungry vocabulary didn’t help with strangers. He stood quietly in the main concourse for a few moments and composed himself for the gauntlet about to be run, willing his hands to unknot at his sides. Then he took a deep breath and walked back toward his ship, ignoring the stares and the whispers.

As he rounded the corner into the secondary concourse which would take him to Belesprit, a hand closed over his shoulder and a gravelly voice said, “How’s about letting an old star skipper buy yez a drink, kid?”

Kehailan started slightly and turned, his eyes lighting with pleasure. “Josephus! Just the man I wanted to see,” he smiled.

“Likewise, I’m sure. What’s on your mind, or should I say, who?”

“Someone whose safety does not merit public discussion, Captain. Can you accompany me to my quarters?”

“Tell you what, Kee, you come with me instead, hm?” One eyelid lowered in a conspiratory wink, and his huge paw gently steered Kehailan ninety degrees around and down another auxiliary concourse toward the agricultural section of the station.

They walked in silence until they reached Josephus’s vessel. The crewman standing guard nodded them aboard, and Josephus took Kehailan to the bridge. “Did Keats tell you we had a medical emergency on board?”

“He mentioned it. I knew you were still in port because of it, waiting for your crewman. Josephus, what is it? Did you see Ardenai when you were on Demeter?”

“I really don’t know, Kee. A’course I’ve gotten forgetful in me old age. Come here, I want to show you something.” Josephus opened the set of metal doors covering the main computator, and then stepped to one side, removing his paunch from the commander’s line of vision. “Tell me what you see.”

“A very, very old navi-psi,” Kehailan said, not sure whether to be amused or sympathetic.

“Very good. Now … fiddle with it a little.”

Kee raised an appraising eyebrow, but he stepped to the keyboard on the bridge console, and began to run a standard navigational program. He stopped, rubbed his chin – ran another program.

“Now tell me what you see,” Josephus prodded.

“A very old navi-psi in excellent condition,” Kehailan said with an admiring whistle. “State of the art SGA navigational data, extended preprogramming capability within the existing system, no extraneous or outdated bits. There’s nothing wrong with … wait a minute … this isn’t SGA navigational stuff, this is UGA! This is what Belesprit has!”

“Right again,” Josephus nodded. “I just wanted to get an expert’s opinion. I didn’t realize I had United Galactic Alliances technology …” he glanced at the taller man from under his bushy eyebrows. “It’s okay to have that, isn’t it?”

“Of course it is,” Kehailan said with a chuckle. “I don’t know why you wanted my opinion. You must have been pushed to the front of a very elite line to have this onboard.”

“Was I?” Josephus asked, and Kehailan’s eyes began to narrow. “Kee, I’ve been in any line I could get into for the last three years to have this machine re-programmed. Old ships keep getting pushed aside, you know. May not last that long, so why bother’s the attitude. My navigational data was so ancient it was practically useless. New routes was out of the question. Now look at this thing.”

Kehailan hiked himself onto the bridge rail and stared into the computation bank itself, almost as though he could make a face appear if he concentrated hard enough. “The two men who boarded on Demeter, and then … did not go with you. What did they look like?”

Josephus pulled his eyebrows together one more time and really, really concentrated, but again he had to shake his head in defeat. “Kee, I have no idea. I think about them … they was tall, one of them had a beard … they were drunker’n hell, but … nothing comes to mind.”

“Why do you suppose that is?”

“That’s what I’m asking you, Kee. That damned adjutant even made me take a Halston test. I don’t know a thing about Ardenai’s whereabouts.”

“Josephus, I think you do,” Kehailan said, and his eyes were twinkling, which made Josephus smile. “I think they stayed on board the whole way here, and I think at least one of them worked off his passage fixing this computator. Do you suppose I could …” he wiggled his fingers graphically, “… check for messages?”

“Only if you’ll tell me the good parts,” Josephus laughed.

“This won’t be nearly that intrusive, but I can make something up, if you’d like.” the Equi replied, “for entertainment’s sake.”

“Please, so I at least think I have a life. Come on over here and sit with me where it’s private.” He led the commander to a small alcove which served as his office, and with a couple of tries, got the door to shut. “I do work on the old girl, you know,” he said a little defensively, gesturing toward two chairs. “What do you want me to do?”

“Just relax. And if you’ve been eating alliums or drinking alcohol, hold your breath,” Kehailan chuckled. He sat down facing Josephus, then he let his eyes close and began to breathe, slowly and deeply. “With me,” he said quietly, and placed his hands on Josephus’ forearms. After a few moments he moved his head slowly until his forehead came in contact with the captain’s, and for those few moments, Josephus could remember every beautiful thing that had happened in his life – he could smell flowers and trees and water – hear the laughter of loved ones, feel warm, female bodies against his … and when Kehailan eased his head away, Josephus felt like he’d been on the best holiday of his life.

“Hot damn, what would you charge me to do that about once a week?” he breathed.

“You’d have to marry me,” Kee said, and sat back with a soft snort of amusement.

“Well?” Josephus demanded, gesturing impatiently. “Was it him? Was he here? Did we have a good time?”

“Ask yourself who else would have that much UGA navigational data in his head, and who could transfer it that fast. As to having a good time, I don’t really think so. You summoned Doctor Keats to treat my sire, not Walter.”

The captain’s eyes grew round with concern, “Is he okay? What was wrong?” He tried to think back to those two men getting on the ship … had one of them been injured? Nothing came to mind.

“An infected wound. We found blood during our investigation of the plantation where he worked on Demeter. But don’t worry. He must have recovered, or your computator wouldn’t be in this kind of shape, would it?” Kehailan reached over and patted the man’s hand. “You’re in the clear for the moment. Don’t worry about my sire. Worry about yourself and your crew. What’s your manifest look like?”

“Machinery belts back to Demeter, why?”

“You are to take them there and unload them as quickly as possible. There will be a load of Chenopodium quinoa going clear to Equus. Again, load quickly. When you are free of the atmosphere, type my mother’s name into the computer, and let the ship take over. When you reach Equus, stay there. Avail yourself of Canyon keep, and enjoy yourself.”

“I don’t suppose you’d care to explain why, would yez, or do you know?”

“I can only assume,” Kehailan sighed, “that you are, or might be, in danger. Another piece of the puzzle has dropped into place.”

“And do we know what that means?” Josephus growled, hauling his bulk up out of the little chair, which squeaked its dismay before trembling back into place.

“Only if we are the Thirteenth Dragonhorse, I’m afraid,” the commander replied, and his eyes filled with worry. He jerked slightly to correct himself, and got a warm, one-armed hug from Josephus.

“Only a mind like your dad’s could come up with something this flawlessly illogical. Come on, I’ll buy you something an Equi can drink … or maybe something he shouldn’t. You look like you could use it.”

“There is one more thing you must do,” Kehailan said, and began explaining as they walked back toward the main concourse.

Sarkhan, too, needed a drink. He waved his right hand, a young woman appeared with a pitcher and two glasses. With a second, impatient wave she disappeared, and Sarkhan turned back to Konik. “You lost him. You had him in the palm of your hand, and you lost him. Your five-year-old grandson … Nokota, isn’t it? He could do a better job than you’re doing.”

Konik caught his breath, then exhaled, trying to make it sound like annoyance. “My Lord Sarkhan,” he said, pointedly not using the Firstlord’s title, “I never had him to lose. Despite the stories, the sightings, the rumors, the accusations, we have never had the man, not even for a single second’s time.”

“No? What about squire … whoever he was? He saw Ardenai.”

“A greedy, fat little dolt who says he saw Ardenai. He has become one of several dozen of his ilk to see the same thing in three different sectors. Your impatience to have the Dragonhorse in your grasp has led us into a hopeless tangle of half-truths … just as Ardenai knew it would.”

“Never!” Sarkhan snapped, stinging from Konik’s comment, and the implied rudeness of bestowing a title Sarkhan considered his onto another, whom he already considered dead. “Ardenai is a man of plodding, unrelenting rationality. He plans when he’s going to take a piss. It is his heritage and his credo. He is totally devoid of imagination.”

“Perhaps he is sure enough of his rationality to know its extensible strength. He may just twist it as he wishes it to go.”

“Too … mundane. Too … lacking in pride for the ruler of a world government. The male who rules Equus is a god, Konik.”

“Beware,” Konik said quietly, “Lord Sarkhan, beware of assuming that Ardenai feels as you do about his office. You desire it above all else, yet it was thrust upon him. He is a man who loves personal freedom. He loves breeding fine horses. He is accomplished in everything he attempts, from music, to teaching both children and horses, to designing computators. What he does, is elegant, and simple. His pride seems to run to his people, not his personal vanity.”

Sarkhan shot the man a nasty look, and rubbed at his upper lip in an attempt to erase the sneer which had formed at Konik’s fawning and treacherous words. “You sound like you want to have sex with him,” he said. Konik’s usefulness had it limits, and when they were reached his treachery would be repaid … about seven times over. Wife, daughters, husbands, grandchildren …the thought of hearing Konik scream made Sarkhan smile. He would speak of this to Sardure. “Ardenai, was bred to receive that office.”

“And to understand it,” Konik replied. “You do not have that advantage.” He lifted a drink from the tray and sat staring through the archways into Sarkhan’s verdant spring gardens. He wondered if the man ever worked in them. Konik did. He loved gardening with Ah’davan in the rich soil of Anguine II. Ardenai gardened. When he blinked his reverie away, he saw that Sarkhan, too, had been staring into space.

“I have spent years … my whole life, as an Equi. I know their ways, and I know their thoughts.”

“No, Lord Sarkhan. You have maintained too great a distance to do that. You know their ways, and how their thoughts manifest themselves in speech or action, but the process itself, you cannot hope to understand. You are a creature of rampant emotion, pretending to be rational. Your opponent is a rational creature, pretending rampant emotion. He has the advantage. He is also a very powerful telepath, probably the most powerful hominoid on Equus. If he so chooses, he has effortless access to places in the mind where you cannot hope to go. If Squire Fidel really did see him, he has trimmed back his ears, and lightened his hair, and grown a beard. He displays his temper quickly in public. He is less thoughtful in action than other High Equi. This is not the Ardenai we have observed. What we have is an Equi pretending to be a Demetrian mongrel, or some other off-worlder. This is more complicated yet. Besides the original process you must now project that to his interpretation of another culture. Now, you are completely backwards, logically. You are Telenir, trying to think like an Equi who is trying to think like an unknown mongrel.”

“Oh, shut up,” Sarkhan muttered. “You think too much and act not enough. What did you find on Demeter? Did you investigate fully? Perhaps you missed something.”

“Assuming that Ardenai had fled, I pursued him rather than seeking evidence that he had been on the plantation. After all, what good is the scent of an enemy when the enemy is gone? It serves only to remind us that we are still behind our quarry.”

“My father thinks you are a warrior,” Sarkhan sneered. “He is a querulous, demented old fool who has hung onto life this long simply because he wants to see me rise to power. And to that end, in his infinite wisdom, he stuck me with you, who are nothing more than a philosopher, who will not draw his sword and step forward for fear of falling on his own blade.”

“I, too, have spent my life among the Equi … as an Equi, and my family for many more generations than yours,” said Konik, and said no more.

A man in the uniform of the Equi Horse Guard came trotting up the stone steps from the garden and nodded their direction. “What?” Sarkhan asked, beckoning him closer.

“Word has reached us from SeGAS-7 that the clipper which Physician Pythos left there has disappeared.”

“When?” Sarkhan exclaimed. “Who took it?”

“No one knows, Senator.”

“I know!” Sarkhan said, rising to his feet. “Again, Konik, we smell the enemy, hm?”

The messenger gave Sarkhan a queer look, and Konik dismissed him with a smile and a nod. “Beware,” he said again. “Never forget which are ours, and which are theirs.”

“Soon, they will all be ours,” Sarkhan laughed. “Konik, you are bumbling this.”

“I am doing what you tell me to do, as is my duty – pursuing dead end after dead end.”

“Perhaps I should take up the chase in your stead,” Sarkhan snapped. “At least I can think and move at the same time. Perhaps I shall defy my father and take my brother Sardure and leave you here to face Saremmano’s wrath.”

“Why don’t you do that,” Konik replied. “I’m sure Ardenai would like that. I’m sure he would like to have you become enraged enough that you forget your duties to the Great House and your place on the Council, and go chasing off. I’m also sure that at such a time the trail would become very clear for you. He’s playing you as beautifully as he plays every other instrument he picks up, and you’re letting him. We are lost if we do not negotiate. My Lord Sarkhan, think! We can yet unite our worlds as brethren and as friends. What could you give our peoples more precious than that? You would be remembered as the greatest of heroes by both worlds. A greater hero even than Ardenai Firstlord himself. ”

“SHUT UP! SHUT UP! GET OUT!” Sarkhan screamed. “Find me that clipper!”

“Certainly,” Konik muttered, and turned on his heel, leaving Sarkhan in hysterics, throwing wine glasses, and ripping flowers from their pots.

“Will they catch us?” Gideon asked, releasing his harness and easing himself out of the seat beside Ardenai. He was still shaky from the acceleration, and placed one hand, as casually as he could, across the back of the seat to steady himself.

Ardenai swiveled in his chair, retracted his own harness, and stretched, locking his hands behind his head and popping his shoulders and neck. “Not until we allow them to.”

The young man paled just a bit, though he didn’t let his expression betray him. “You mean you’re going to let them capture us at some point?”

“We must at least let them think they have a chance,” the Equi said. “Otherwise they may grow discouraged. Don’t be concerned, Gideon, this is a very fast ship and really quite luxurious.” He took his hands down, rolled his head on his neck, and closed his eyes. “The vessel will fly itself. I believe we should have something to eat, take a nice long bath, and get some real sleep for a change.”

The boy’s eyes – now a pale, leafy brown rather than brilliant, foxy gold – Immediately lit up. “Food sounds good,” he said. “Actually, a big, thick, juicy steak sounds best. But since I know Equi are vegetarians, I don’t suppose there’s meat on board.”

“Don’t be too sure,” Ardenai replied. “My personal physician used this ship last, and he is of the most ancient order of Equi, the serpents of Achernar. Perhaps there’s a nice Declivian tree toad stored somewhere as a snack. That would be in one of the lavages, where there’s water. Failing that, you might find a cage of rodents under one of the beds. They’re back that direction. We’ll sleep in the forward stateroom, so we can hear the equipment. You might as well take your traveling pack with you as you go. Your bed is the one pushed tight against the wall. Main lavage is clear to the back.”

“No eggs? An omelet sounds nice.”

“We don’t eat the unborn, either.”

“You, are sick!” Gideon laughed, picking up his pack and heading through the door Ardenai had indicated, “And it’s no act, either. You have a genuinely heartfelt sick sense of humor.”

“You wound me,” Ardenai called after him, crimping a grin. “To be honest, it wasn’t so much a moral thing as an environmental decision. Raising meat is hard on the planet, and it’s also hard for us to digest. We tend to be grain eaters, so it was an easy choice.”

It was silent for three or four minutes before the boy returned. “An environmental decision,” Gideon said, picking up the conversation, “that’s all you had to say in the first place. Did you know … there’s a great big pool of water back there? It’s sunk down into the floor and it has a kind of a glass sheet over the top of it, and it seems to be in some kind of a vacuum that would break if you opened the door.”

“That’s to hold everything in place if the ship rolls over. We Equi take our bathing seriously,” Ardenai said. “Are you ready to try Equi food?”

“Absolutely. I’m hungry enough to eat just about anything.”

“The best time to be introduced to an alien cuisine,” Ardenai responded. He stood up, and gestured Gideon toward the living area of the ship. There was no real galley, but a shiny black machine an arm’s length, a man’s height, which dispensed alcibus and other vegetable matter in whatever shape and flavor one desired. Ardenai spoke to it in a series of sharp glottal clicks which had little resemblance to speech, and it clicked back. Gideon was fascinated.

“Are you speaking the machine’s language?” he asked.

“The machine is speaking mine,” the Equi replied. That is a very obscure form of ancient High Equi. Few but the most serious Equi scholars ever hear it. My son says this form sounds more like UGA computator speak than actual human speech, and I think he’s correct.”

“I’m honored,” Gideon said. Ardenai turned to look at him, and the youth was absolutely serious. “I am honored, just to … be with you, to see a side of you most people can only guess is there. It is something I will remember always.”

“Thank you, Gideon,” Ardenai smiled. “I hope always is a long time. It does not please me to have endangered you.”

“I don’t mind,” he said, almost wistfully. “I enjoy … having purpose.”

“Well said,” the Equi nodded, and reached for the plates coming out of the dispenser. He put one of them down in front of Gideon, then sat down with the other. “Try it,” he said, and picked up his eating sticks.

“You first,” Gideon said, “just in case this is part of your sense of humor.” He paused a moment and screwed his face up a little. “He … doesn’t really eat tree toads, does he?”

“Oh, absssssolutely,” Ardenai chuckled.

He had taken a couple of bites when Gideon finally picked up his sticks, held them as Ardenai demonstrated, and tried some for himself. “This … is good!” he exclaimed, and fell to it as though he were starved, which in retrospect, he probably was. It had been more than a day since they’d sat down to any kind of meal.

It made Ardenai feel guilty yet again. This was a growing boy. He needed food, and rest. Keats may have been right about the propriety of leaving him, but with circumstances what they were, Gideon was safer here, where Ardenai could protect him.

The Equi snorted soundlessly with amusement at the obvious lie he’d told himself. He wanted the companionship of this handsome and promising young man, it was just that simple. Any danger, they would face together.

“What is this called?” Gideon asked, between mouthfuls.

“It is what we call kukkuk.” He pronounced it more slowly. “Kuk – kuk.”

“What does that mean?” Gideon asked.

“This,” the Firstlord chuckled. “It’s a nonsense word. Kukkuk is made with various vegetables, herbs and oils that are quickly shaken over a very hot fire. A lid is put over them, they are allowed to steam to release the juices and then poured over noodles which can be fried crisp or boiled to be soft. They’re made from alcibus, or grain of one kind or another, which is what Josephus hauls to Equus for us. We eat the grain and so do our horses. We grow our own, but we import some as well, for the sake of trade.”

“He really likes you,” the boy said, but his thoughts were on food, and he went back to eating with such gusto that it made the Equi smile just watching him.

This was the dish he’d used to introduce his young bride to Equi food – real Equi food – not the kind she was used to getting on Terren. She, too, had smiled, and said it was good. With her, it had all been good. Ah’ree … he could still see her, coming to him on her father’s arm, brave enough to leave the world she knew and go with him to a world her parents had only talked about. Ah’ree, Beloved of God, whose name was a fragrant sigh across the endless, night-swept grasslands of Canyon keep. How willingly she had come to him – how sweetly she had given herself to him in the warm darkness – bringing to his bed such gentleness as he had never known, and into his life, such love as he could not have imagined existed.

“Thinking about your wife?” Gideon asked quietly, and even so his voice made Ardenai start. “Josephus said she was beautiful.”

Ardenai nodded, leaning his chin on the heel of his hand and gazing at something only his mind’s eye could see, his dinner forgotten in front of him. “She was my good friend of many years. No one will ever replace her.”

“When …” the young man hesitated, but the Equi knew.

“Two years. A little over.”

“Have you thought about remarrying? I mean, it seems like as Firstlord, you’ll need a wife.”

“I had not planned to remarry, ever,” he sighed, “nor do I want to. But, as you assume, those who rule must be paired. As a matter of fact, the Dragonhorse must have three wives, and if I do not choose a mate, my dam will choose one … or more of them … for me.”

“Now that sounds wonderful,” Gideon snickered, but it did nothing to relieve the pain in Ardenai’s eyes. “What will you do?”

“Cross that bridge when I come to it,” he said, making himself sound matter of fact. “Right now having that as my major problem sounds rather inviting.” He picked up his sticks again, but his food was cold, and his appetite was gone. No, the thought of another wife was not inviting … the thought of finding a mere woman to replace Ah’ree. When she had gotten sick, was wasting away, when Pythos could do nothing but weep great tears of agony to be helpless, Ardenai had gotten down on his knees and begged Eladeus to spare her life. In the end, he had begged The Creator Spirit to take him instead, or to take him, as well. But in the brightness of a spring morning, with sun streaming into their bedchamber, he had held her in his arms and known she was gone from him – his laughing bride – his beloved bedfellow. And he … was left behind.

He realized Gideon was gently sliding the plate away from him. “I’m sorry,” Ardenai said, dragging the cuff of his tunic across his face. “I must be very tired. I should go to the lavage pool and bathe. Would you like to take a bath with me?”

The boy reacted as though he’d been slapped – took a staggering backward step – eyes wide with fear. “No!” he gasped, “Please …”

And in the same breath, Ardenai, as horrified as Gideon, was saying, “I’m so sorry! I meant no offense! Please, don’t be alarmed.” He had better sense than to reach for him, and Gideon drew a shuddering breath and came to a balky, reared-back halt like a frightened colt. “Please, be calm. I didn’t mean to scare you.”

“I … I’m so sorry,” the boy said, and it was a moan of pure misery. “I … I’m just so sorry. I thought … I mean, I didn’t think, because I knew you wouldn’t …. Oh, El’Shadai, I am so sorry. It was just a reaction.”

“I should have thought before I spoke,” Ardenai soothed. “We Equi bathe and groom one another as one of our fondest social traditions. I forget, my friend, that you are not Equi. Forgive me. Not for anything would I have shocked you in such a manner.”

Gideon nodded and tried to smile, but there were such tears standing in his eyes that he dared not blink for fear of spilling them and seeming an even bigger fool than he already felt. “I’ll just put these dishes away,” he managed, and nearly ran in an effort to hide himself and his shame.

To give the young man some breathing room, Ardenai excused himself and went to the bathing pool. Even on a fifty foot clipper, it was a spot of luxury. It extended the width of the ship, fifteen feet or so, with a semblance of trees, grass and stone, the three most important elements besides water in Equi design, and moving images which gave it the sense of being in a forested grotto. He retracted the cover, closed the door behind him, and dropped his clothes into the refabricator.

Two walls were living projections of the Equi landscape, the third was a reflector, and Ardenai stood contemplating himself at full length. He’d lost a little weight, but that was to be expected. The face with its short-clipped beard and softly curled brown hair, while not unattractive, was unfamiliar, and he did not dwell on it. His poor ears, he couldn’t bear the sight of. His chest, tanned from working without a shirt, was darker than his long, straight legs. He’d always been grateful in a desultory sort of way not to have inherited his sire’s legs, which tended to be a bit bowed; horseman’s legs, his father had joked, always ready to ride. Now, he knew why he’d not inherited them. Krush was not his sire. Nor was Ah’rane his dam. Funny. People told them how much they looked alike, told Ardenai and his sister, Ah’din, how much they looked alike. And they were no relation at all. An eagle’s chick had been plucked from its aerie and tucked into the nest at Sea keep … an old Corvus eagle … and Krush and Ah’rane, in their goodness, had raised it as their own.

He looked at his genitals, rather flattened from being confined to trousers, and marveled that within his loins dwelt the purest get of Equus. Him. Ardenai. With that phallus fully extended from its protective sheath, he had implanted into a woman he did not know the next high priestess of Equus. He stared at the beautiful pythons which, thanks to the skill of Doctor Hadrian Keats, once again wrapped his arms in intricate green and gold coils. Under those pythons, were the Arm-bands of Eladeus. He, Ardenai … the man who raised horses for the Great House, who rode all day, and mended fences, and delivered foals and cleaned manure from his boots like every other horseman. He, who gathered young children around him for their lessons, and cajoled and threatened and praised like every other teacher from the time of the troglodytes, who understood how computators worked better than he understood how the mind of his son worked. He, who ate and drank, who laughed at inappropriate times, cried at inappropriate times, and made love, and became angry and frustrated, who needed sleep, and to relieve himself of bodily waste, who got his clothes and fingernails dirty in the course of a day’s work, who needed to brush his teeth and get his hair cut, who stank if he didn’t bathe … he … Ardenai … was Firstlord Rising of Equus. He corrected himself. He was risen. He was Firstlord. He was The Thirteenth Dragonhorse.

This, then, this rather ordinary reflection of a man, was what absolute power looked like? This was the man who had to stay alive to pass the pure seed of Equus to noble women he did not know? This shaggy-haired individual who definitely needed a bath? Ardenai found himself shaking his head, and realizing that, on top of everything else, gods got cold if they stood around naked long enough.

He lowered himself into the hot water with a groan of pleasure, scrubbed his face, his hair, his body, and dropped his intromittent organ to clean it, wondering if it would ever be used for pleasure, for passion, for love … ever again. He sighed, closed his eyes, and leaned back. Who had that young woman been, he wondered, whose virginity he had taken? How had she felt, hearing the great stone walls reverberating, a daughter for Equus, a daughter for Equus ….

Very impressive. All of it. A ceremony ancient beyond memory. And Ardenai had been on his feet as was proper, dressed in a long, soft robe of richest blue-black horsehide, drugged just enough to be able to concentrate over the terrible pain in his arms … and in his heart. He could feel the round, brocaded edge of the priapic bench, which hit him just above mid-thigh – the extension which he straddled – representing the erect male phallus, the bench upon which Equi virgins had been penetrated from the beginning of history, an item passed down through families as an heirloom … the same kind of bench upon which he had placed Ah’ree on their wedding night. But there had been no curtain between them and no robes. He had lain across her back, warm skin against warm skin – caressing her breasts, using only his lips against the back of her tender neck, not his teeth – penetrating a little at a time, using his hands to steady and reassure her as he brought her to climax.

This very young priestess, he had not seen, except the part of her that was on his side of the drape, nor had he caressed her with his hands, nor comforted her with words. She had been stationed like a trussed-up filly, waiting for him on elbows and knees, her legs and thighs encased in superbly tanned horsehide. Even her feet were covered. Only her primary sex organs were exposed. She was not to be regarded as a person. She was a vessel. She had been wet with full heat, drunk with passion despite her virginity, and she had writhed and cried out, and pushed back wildly against him, demanding penetration. He had wanted to lean across her back and sink his teeth in her neck, but instead he had seized her by the tops of her thighs to control her, and pushed hard to break her maidenhead. She had cried out with pleasure or pain or both, and her rhythm had settled enough that he could control her. At the moment when her cries and the throbbing of her canalic walls told him she was in orgasm and could not resist him, he had ejaculated … only female sperm … and withdrawn, without a moment’s pleasure. He’d tucked himself as tightly and as quickly as possible, and she had moved forward into the curtain, and vanished from his life.

And his beloved Teal had reappeared, offering support and a drink of cool spring water. It had tasted … so good. The warm support of his arm had felt … so good. He could not be dead. He could not. Not that man. Not that life. Not that light.

Ardenai felt better for the bath if not the reminiscences, showed Gideon how to use the equipment in the room, and collapsed into a real Equi bed, long enough and wide enough for him to sprawl out in, with warm, soft coverings of the finest wool, which smelled of grass and leaves, and home. Without the need for lecturing himself to do so, he fell into a deep, untroubled sleep.

Gideon was awakened many hours later by the urgent calling of his bladder to be emptied, and he swung his legs over the edge of the bed and hurried to the lavage. He was used to urinating outside, against the side of a building or behind a tree. This, was luxury. He was warm, he was dry. He could have sworn the sun was up. There was the soft fragrance of meadow grass and the quiet, faraway sound of birds singing amid rustling leaves. When he had finished, a small, damp towel presented itself for him to clean himself with, and when he let go of it, it vanished back into the wall. He wondered if he was the only one who would use it, if that towel was just for him. The toilet flushed itself, and he wandered back to bed. He sat on the edge of it and ran his hands over the mattress and the amazing clothes which covered it. He had never slept anywhere so comfortable in all his young life. And the fabricator thing Ardenai had shown him! Before his bath he had put in old, ragged clothes, stolen from some denizen of Squire Fidel’s bunk house, and by the time he was bathed he’d got back new. He’d even chosen the colors. Light brown trousers and a deep blue shirt. Both very plain, like a uniform, but comfortable and clean … and new. He’d never had anything new.

He looked toward the other bed, and saw Ardenai, still sound asleep. He was spread-eagle on his back, one arm flung to the side palm up, the other tossed casually across his bare chest. His breathing was slow and even, indicating deep sleep. Something crossed his mind as he slept, perhaps some part of his dream in which he needed to participate, because his body jumped a little, and he twitched his head before settling back into his pillow.

It occurred to Gideon that Ardenai was helpless, that he could pick up something and bash the man’s head in, or stab him, and the Firstlord of the most powerful league of affined worlds in the galaxy, would be dead without ever waking up. Along with the feeling of horror which accompanied Gideon’s admission to himself that he’d ever thought of such a thing, came the pleasure, and the weight of knowing that Ardenai trusted him enough to sleep, really sleep, in his presence.

There were two other sleeping compartments aboard besides this space. He could have assigned Gideon to one of them, but he hadn’t. He had said Gideon was his friend. Gideon sat for some time and thought about that, trying to get his mind around the concepts of friendship and trust, because, since they had been offered him, they were now expected of him, and he wasn’t quite sure what they meant.

What must the man have thought last night, Gideon wondered, and how would he ever be able to approach the subject with him? This was something beyond the Equi’s ken. Worldly though he was, he was also privileged – a prince from a royal house on a planet where royalty still meant something positive. So … why had he chosen to befriend a ragtag boy? It was indeed amazing, because it seemed so sincere on Ardenai’s part.

As for Gideon, he worshiped the man. He loved him so much it made him ache inside. When Keats had suggested that Ardenai leave Gideon behind, it had been all Gideon could do to keep from running into the room and knocking the doctor flat on his back. That image made Gideon snicker, and the snicker made Ardenai shift a little, so Gideon got up and padded out into the other room to continue his musings and check out the food replicator.

When Ardenai awoke things seemed much brighter, heightened by the enviro-psi’s generated change from night to day and the pastoral scenes of his homeworld which made the walls of the ship recede to nothing. He lay on his side, cheek on his forearm, and daydreamed, something quite apart from his usual train of thought. He could close his eyes and see the cliff falcons wheeling above him against the cobalt sky, hear their piercing whistle, take a deep breath and fill his lungs with air so warm, so light, that it infused one’s being with health and hope. Ah, to be home at Canyon keep.

Something jarred him mentally, and he sat upright in bed, just as Gideon came in from the galley. “I hope I didn’t startle you,” he said quickly. “You seemed to be stirring, and I thought you might enjoy something hot to drink.”

“Thank you,” Ardenai replied, dragging his hands through hair which had grown even longer and rougher over the last many weeks. Soon, he’d be able to braid it back again, and feel a little more like his old self. “You did not startle me. I was just entertaining a thought which hadn’t crossed my mind before. I was lying here, thinking that I hardly recognize any aspect of myself these days. Not physically, not emotionally. And it suddenly occurred to me … that Kehailan felt like this when he was growing up. This is the feeling he was trying to describe to me – the feeling of being his mother’s son, and mine – a product of two cultures which converge and diverge at odd times and odd angles, and he was trying to make sense of it all and find a niche for himself, and I was no help at all.”

“Maybe not, but you need to realize that he was born facing the problem which you find so novel. And he had two good examples, you as an Equi, and your wife raised as a Terren, even though she, too was half Equi. Which brings me to this,” Gideon sighed, sitting back down on his bed, “I owe you an apology for last night.”

“Do you?” Ardenai asked, sipping at his drink. He flexed his hand away from the warmth of the cup, and the python on his left arm undulated ever so slightly, reminding Gideon of whose presence he was in.

“Yes, Dragonhorse, I do. I pried into a very personal aspect of your life, and I didn’t even realize I was doing it. Your wife … tends to stand in your eyes, sometimes. I’ve come to recognize her. Nevertheless, I should leave her there, in your private thoughts. Asking you if you were going to remarry was a rude, unfeeling thing to do. I’m sorry.”

“The apology is unnecessary,” Ardenai assured him. “No offense was taken. Of all the beautiful things I have to share, my memories of my wife and our life together are most precious of all.”

Gideon sucked in for air and blurted, “Then why don’t you share your memories of her life? You’ve never told me one thing about what she was, what she did, what she liked. All you have ever mentioned is her death. Surely she was more to you than a representation of death and loneliness.” He stopped speaking and felt the soft, sooty black of Ardenai’s eyes going right through him; that slightly cocked head like a bird of prey. A dozen times already he’d regretted making that crack about Corvus eagles. What an enigma this man was. What a treasure to be unearthed a bit at a time and studied. Yet, at the moment, Gideon was the one being studied – intently, unsmilingly. As was his habit, he reacted to shift the focus from yet another stupid utterance on his part. “Why did you let me believe that you were stealing this clipper?” Ardenai sipped at his drink and said nothing, his eyes never wavering from the boy’s blushing face. “If you’d told me it was yours I wouldn’t have asked you that question about ethical behavior. I would have known.” “Precisely,” the Firstlord said, and the eyes began to dance with amusement.

“It’s a game with you, isn’t it, seeing why people think the way they do?”

“No, not a game. An avocation.”

“So I get to sit here and slit my own throat with the sharp edge of my wagging tongue?”

“I see you got the nutri-comp, the replicator, to work for you.”

It was Gideon’s turn to cock his head and study his companion. “Work? You mean the food dispenser? I asked for two cups of hot cinnamon orange tea. It gave me two cups of hot cinnamon orange tea.”

“What made you think, when I had spoken to that machine in High Equi, that you could speak to it and make it function?”

“You. I assumed you, or someone like you, programmed it. ‘The brighter the mind, the simpler the machine.’ That’s an old Declivian saying.”

“You honor me,” Ardenai said. “When I have dressed and said my morning prayers, and we have checked our navigational extrapolations, we shall settle ourselves over breakfast and discuss old Declivian sayings, and Declivians in general.”

“You’re going to eat me, aren’t you?” the boy gulped. “I should never have said those things about your wife. I can’t begin to fathom your grief, much less analyze it …”

“If you apologize one more time for speaking your mind, I will eat you,” Ardenai warned, though his eyes were smiling. “Do you think you are the only one of my friends to sing me this particular song? I know I have to get on with my life. Even if this … epiphany of identity hadn’t come along, I’m still young. If I were Declivian, or Terren, I’d be somewhere in my late thirties. I still have almost two thirds of my life to live. And you’re right; I do spend too much time dwelling on Ree’s death and not enough celebrating her life. I knew from the first day I saw her and fell in love with her on the spot, that I would outlive her. Because I am High Equi I will live at least two hundred and fifty years. She had Terren blood. Not a lot, but enough to shorten her lifespan. She would have been lucky to live a hundred and fifty years, even if her health had not failed her. I knew I would watch her grow old and die – in my head I knew. I had not counted on the things she would do to my heart over the years, how dependent upon her I would come to be.”

“Please, Sir, before you eat me, satisfy my curiosity. What was she like when she walked, and breathed, and had and gave life? How did you meet her?”

Ardenai set the cup aside and flopped back onto the bed with a chuckle. “I was at my first Terren posting, the Pacific Northwest Island Province of Quadrant Two, in an ancient, ramshackle town called Sealth, which the SGA wanted to rebuild into a jurisdictional headquarters. The mountains up and down the chain were still smoking from the last big eruptions, the wildlife and the ecology in general had suffered greatly. There were archeologists doing deep water excavations of the most ancient Old Earth city, and I was curious, so I went down to where one of the digs was based. I was rock-hopping on one of the lava flows that had run into the sound, and here was this silly girl, trying to rescue a baby seal that was caught in one of the fresh lava pockets; very sharp stuff. The baby’s mother was huge, and she was none too happy, but the tide was coming in, and if the baby stayed in that pocket, she’d be beaten to death by the waves … so here was Ah’ree, trying to figure out how to keep her footing on the lava, fish out this little seal, and avoid having her leg ripped off by Mother. I hadn’t been there two seconds, my feet had not stopped moving, and she looked up and said, ‘Well, are you going to help this poor baby or not?’ I was … impressed. She didn’t ask if I was going to help her, she asked if I was going to help the animal. So I straddled the pocket and lifted out baby and set her in the sand, and then grabbed Ree and ran before the mother seal could get her teeth in us. And when we were a safe distance away, I noticed … this girl was pretty – exceptionally pretty – and she had lovely, Equi ears peeking out of her hair. Then, she looked up at me and she smiled and said, ‘Would you like to do this again sometime?’ And I told her that if she was involved, I most assuredly would. Eight months later we were married back on Equus. Very short courtship, but it worked out well.”

“Wonderful! Did she tell jokes?”

“Terrible jokes. Lots of them, usually about ducks. She was very fond of ducks, and kept them as pets. And she enjoyed a practical joke now and then, as well. She also enjoyed tickling people who were trying to sleep.”

“Did she like horses?”

“She was Equi.”

“What else?”

“She … danced like fairy-dust in the wind, and played the harp key and the guitharp, and the pipes. She sang in a high, clear soprano … but it wasn’t piercing. She loved animals and children and defenseless things in general. She wrote beautiful poetry. She was a tireless gardener, and she learned to make the best kukkuk I’ve ever eaten. Which reminds me, I’m starving. I will dress, we will settle ourselves at the table, and, since I have discussed my life with you, we will discuss Declivis, and Declivians, and you, my friend.”

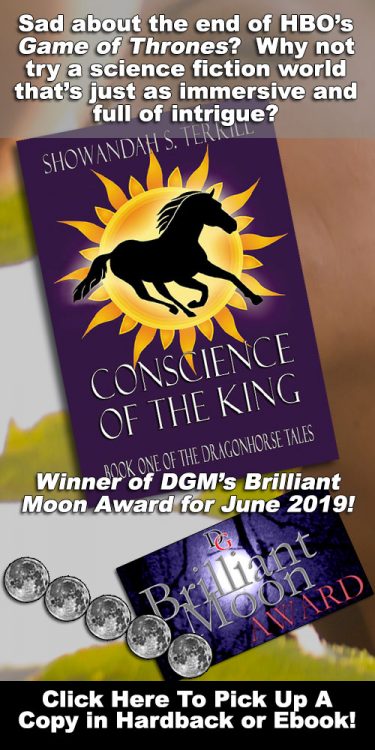

Check back next week for the next chapter in this exciting serial from the Dragonhorse Rising universe. To learn more about Dragonhorse Rising and the world of the Equi, go to: http://www.dragonhorserising.com . You can also follow them on the Dragonhorse Rising Facebook page.