“Simply, I do not desire a war,” Ardenai said, side-arming a rock with the force of a slingshot against the wall of the ravine. “I want Sarkhan to face me armed only with his wits. On Calumet, that’s all he will have.”

“He can bring a whole army, though,” Gideon panted, crunching along beside his long legged companion. He’d had no idea that Ardenai’s idea of stretching their legs would involve a brisk jog in hundred and ten degree weather. The sweat was rolling into his eyes, and the fact that Ardenai reveled in such misery did nothing to make Gideon any happier. “Can we turn back?”

“From which point?” the Firstlord teased, but he saw that Gideon was suffering from the heat, and he turned even as he spoke. “There’s some shade,” he said, nodding toward an outcropping of rock. “Let’s rest a few minutes before we return to the clipper.”

Gideon scrambled in the rattling shale and plopped gratefully in the shadow of the rock. The Equi remained in the bottom of the ravine for a long moment, head cocked, nostrils flaring, eyes moving along the rim of the wash, then climbed up and sat beside Gideon, producing a water bottle from his hip belt.

“Something wrong?” Gideon asked between swigs.

“I am not sure,” Ardenai said. “Catch your breath and we’ll go back.”

“What do you suppose is out there?” Gideon muttered. Ardenai was clearly uneasy, and when an outdoorsman was uneasy outdoors, there was reason to be concerned.

“It is not Sarkhan and his army, if that’s what’s worrying you,” the Equi replied. “Nor will we face an army on Calumet. There are strict entry quotas. No military personnel are allowed on the planet’s surface in units larger than a squad of twelve, and no combined force may consist of more than four squads, or one platoon. That’s only …”

“Forty-eight people,” Gideon said quickly. “Now, Ardenai, how can they possibly control that sort of thing?”

“They do not. The atmosphere does. Remember, nothing works on Calumet. You can take a ship into the atmosphere if you unconcerned about how hard you land. Scrambleshafts won’t work, either. The only way to enter Calumet’s atmosphere is through a CAC – a Controlled Atmosphere Corridor. It is also the only way out.”

“Do you suppose one could soft land a troop carrier using parachutes or somesuch?”

“Given long enough to plan it, probably,” Ardenai replied hastily. “Come on, let’s go.”

He stood up, skidded down the shale and lit out at a dogtrot with the Declivian close behind him. “Gideon,” he said, “Run!”

They hadn’t gotten more than a hundred yards or so when Gideon yelled, “Ouch!” and clapped his hand over one shoulder. Ardenai spun around in alarm, and Gideon’s face was tortured. “Something … is stinging me,” he groaned. “It hurts like fire!” and he collapsed in Ardenai’s arms.

In an instant, Ardenai had jerked the dart from Gideon’s back and cast it aside. He raised his head, swiveled on his haunches, and took a dart in the fleshy part of his left breast. Another instant and it, too, was gone and the pultronel in Ardenai’s belt was in his hand as he faced the figures coming down the ravine. He set the weapon on stun and pulled the trigger. Nothing happened. No charge. It had ceased to function. “Well … perfect,” he said. Another dart struck him, and he went down.

He came to lying in the shade of the clipper. His muscles ached and he felt weak all over. Gideon was still unconscious. Ardenai rolled over to touch him, and a broad-bladed spear plunged into the sand inches from his face. Something muffled and guttural was said, and he was jerked to a sitting position.

He looked up and saw only shapes, dirty white against the blinding sandstone backdrop. He lowered his head gingerly into his hands and sat waiting for his vision to clear. There were voices, several, muffled by layers of cloth. Again he raised his head, and was yanked into a standing position. The robed figure pushed him against the side of the ship and leveled a spear at his guts.

“You have nothing to fear from us,” Ardenai gasped, and immediately had to choke down the ridiculous urge to laugh. That was probably the stupidest thing he’d ever said in his life. Even with only their eyes showing to reveal their intent, these people were obviously not afraid.

Gideon was hauled to his feet and slammed against the clipper next to Ardenai. He slumped, Ardenai reached to steady him as reflex, and the spear’s point went through his tunic to prick his flesh. He spread his hands and flattened his back against the spacecraft.

“What’s … going on?” Gideon mumbled.

“To borrow a phrase, we are in big trouble,” Ardenai said softly. “Don’t make any sudden moves.”

“Have you tried talking to them?”

“About what?” the Equi hissed peevishly. “You think they’d like to learn a song? Establish a Consulate?”

The warriors began to mutter among themselves and gather close around the prisoners, pointing at Ardenai. The Equi looked down, and where he’d been poked with the spear tip, there was an ooze of blood, obviously blue against the unbleached tan of his muslin tunic. “El’Shadai,” Gideon whispered, “they know you, First…”

“Stop!” Ardenai hissed. “I doubt they know me, but I don’t want to take any chances. I think it’s just the color of the blood that’s interesting. I hope they don’t decide to see how much I have.”

“They’re huge,” the Declivian groaned. “They’ve got to be over seven feet tall, all of them, and they smell like …” the word escaped him. “They smell musty, like animals. Think they’re going to kill us?”

“No. Logically, if they were going to kill us they’d have done so by now … unless they want us for some kind of a sacrifice to the full moon, but I doubt that.”

“Then what do they want, and stop with the wild speculation.”

“Us, obviously.”

“Why?”

“Gideon, I’m a teacher, not an anthropologist. Just be quiet, mention no names, and see what they do. Are you carrying identification?”

“No.”

“Good.”

“Maybe they want the ship.”

“Just what every stone-age nomad needs, a spaceship. No. They can only want that which they can comprehend having. That, my unfortunate companion, is us.”

One of the men grabbed Ardenai’s shoulder and gave him a savage push down the ravine, gesturing with the spear. Ardenai took a few steps and turned. The swaddled figure gestured again and they all began to walk, dragging the groggy Declivian between two of them. All that afternoon they walked without water or rest, until even Ardenai was stumbling from exhaustion. At dark they were given something to drink and bound back to back with their feet tied.

“Maybe we can get away while they’re sleeping,” Gideon whispered.

“What a good idea,” the Equi whispered back. “We can take turns hopping backward. By morning we could be several hundred yards from here.”

“I can’t believe you’re going to give up at this point.”

“For now, we have to give up. That does not mean it’s permanent. Slide forward a little and rest your head on my shoulder if you can. You’ll feel better if you sleep.”

“What about you?”

“I’ve had plenty of deep sleep the last couple of weeks. I’ll watch, and listen, and see what I can piece together.”

Gideon settled himself, and after a while his even breathing told Ardenai he was asleep. These desert people, who hadn’t said ten words all day, didn’t say one word all night. They simply ate, kicked out the fire, and slept on the ground.

By dawn it was bitterly cold, and Ardenai was the one who suffered. They were untied, yanked to their feet, and forced to walk, though this time they were left together. They weren’t allowed to speak, but they were allowed to support one another. Ardenai could barely stay on his feet until he’d warmed up from walking. Then, as the day progressed and the sun beat down, it was Gideon who needed a guiding arm to steady him. By evening, they were carrying each other, moving forward by sheer strength of character. Again they were watered and bound together. Gideon was almost instantly asleep, and Ardenai was grateful. The heat was killing his young friend. Again he watched and listened, but nothing was said. He couldn’t help wondering what was under those robes. Could be anybody … or anything.

At high sun the next day they reached a village constructed of mud bricks, and though they had been moving into an area that seemed ever more desert-like, Ardenai could hear and smell the sea. The village was built around a square, and that is where they were taken.

“Aw … look,” Gideon whispered, jerking his chin, and Ardenai nodded.

“Slave traders.”

They were taken into the cool interior of a house, pushed onto the floor, given food and water and allowed to rest. They didn’t even discuss the reason why. They both knew they’d bring a better price if they looked strong and healthy. Ardenai poured a little water into his hands, then patted it gently on Gideon’s cheeks and forehead, wishing it was iron integument. Every inch of the boy’s face was blistered, and so swollen he could hardly be recognized. Ardenai wondered if he looked any better, and if he should be glad if he didn’t.

Gideon stretched out on his back on the cool floor and went to sleep, and Ardenai, having made absolutely sure they were unwatched, pushed his tunic off his left shoulder and looked at the wound on his arm. It wasn’t pretty, and it wouldn’t bear close scrutiny, but it would probably escape immediate attention. It was discolored, but no gold showed through. The swelling from the pouring of the bands had been gone for a season or more, and it looked like what it was, a freshly healed knife wound. He readjusted his tunic, closed his burning eyes, and sat listening to the sounds outside.

By the time they were taken from the house the Equi Firstlord knew to whom they were being sold, and why. They were big, and strong. If they passed inspection they’d be sent to the cleomitite mines on Calumet. A tall, dark-skinned man whose features were largely hidden by the brim of his hat jabbed Ardenai and said, “What are you?”

“Not a criminal, if that’s what you’re asking. We …”

The man swung suddenly with the flat side of the clipboard he was carrying, aiming for the Equi’s face. He was met instead by Ardenai’s right fist, which shattered the clipboard and sent the man staggering backward.

“Have it your way,” he said. Someone grabbed Ardenai from the back, and the tall man put his fist into the Firstlord’s mouth. Blood spurted from his lips, and the man said, “Equi mongrel. That’s what I was asking.” He turned to Gideon. “You got blue blood too, boy?” Ardenai held his breath. An Equi mongrel didn’t mean much – but it was a good guess. An Equi mongrel with a Declivian boy … things could go very wrong at this point.

Ardenai focused his thoughts. Don’t mention Declivis.

Gideon started slightly, then shook his head. “I’m a Coronian cross,” he mumbled.

“What’s the mix?”

“Who knows,” Gideon shrugged. “My mother fucked anything and everything.”

The slaver didn’t question it, and without the bright gold eyes there was little to recommend the boy as Declivian. The other defining Declivian feature, that very deeply cleft and bony chin, was also missing on Gideon. He had a bit of a dimple, nothing more. Ardenai breathed a silent sigh of relief.

The man left the boy alone and returned to Ardenai. “You, are one wicked looking sonofabitch, but I’ll bet you’re strong. You got a name?”

“Grayson,” Ardenai muttered, blotting at his mouth with the back of his hand.

“What about the boy?”

“Reed.”

“Known him long?”

“I won him in a poker game two years ago on Corvus.”

“How’d you end up here?”

Ardenai glared pointedly at the robed figures and said nothing. “You’ll come around,” the man laughed. “I’ll take ‘em both.”

They were herded with several other men into the stinking hold of a freighter, chained to the sides, and left in utter blackness and near freezing cold. Mercifully, they were chained close together, and by only one wrist. Ardenai and Gideon sat huddled together, conserving body heat and trying to buoy one another’s spirits. Not knowing what the others might understand, they said nothing. At last Gideon’s head relaxed against Ardenai’s chest. Ardenai tightened his grip to hold the boy in place, and lost himself in thought.

Endlessly they traveled. Endlessly, until Ardenai quit shivering and lapsed into a torpor that was near unconsciousness. He didn’t realize they’d landed until he felt Gideon rubbing him none too gently back to life. “Come on!” Gideon whispered, “Come on, dammit, move!” Ardenai forced himself to do so, gasping with an effort that was almost beyond him.

They were unchained and dragged one at a time into the blinding sun of Calumet to stand inspection, while the tall man presented false documents saying they were criminals sentenced to hard labor. Ardenai, with his wild hair and beard and battered face, was totally unrecognizable as the man who had left Equus seasons before. Gideon, with his blistered and peeling skin and his eyes swollen nearly shut, had lost his identity as well. They were loaded with six other men into a horse-drawn wagon and hauled twelve hours to the cleomitite mines of Baal-Beeroth.

By now it wasn’t even real for Gideon. It was just another nightmare of the kind he’d had all his life. He sat in the wagon next to Ardenai and wondered how this noble person, bred to wealth and power and things of the intellect, had survived with his wits intact even this long. As if in answer to his thoughts, a hand closed over his, and Ardenai’s voice said, Courage. Every step now is one toward freedom. Don’t give up. Gideon looked at him, but the Equi’s lips had not moved.

Two hours after dark they were unloaded, taken into a long, dirt floored building, issued a bowl, which was empty, a wooden spoon, and a dirty, straw-stuffed mat to sleep on. They collapsed, without a single word between them.

The news arrived in all three camps almost at the same moment, touching off pandemonium which was instantaneous and complete. “The clipper belonging the Great House of Equus has been found on Corvus in Sector three. It is for sale to the highest bidder.”

Sarkhan went wildest and screamed loudest. Again the Equi had eluded that fool Konik. What if he’d been taken by pirates? What if those armbands were decorating some barbarian’s lodge pole? In a frenzy, Sarkhan called for a ship to be made ready. This could no longer be left to underlings. Ardenai Firstlord could not be found, nor the snake who had supposedly gone to some medical conference and left that clipper at SeGAS- 7. He wasn’t convinced that the lying little captain was dead, either, or that so-called kinsman of Ardenai’s, deadly bastard that he was. What if they were converging somewhere? They had to be! Where in kraa were they?

The high priestess sat with her fingers together and read the uncertain faces of the Privy Council. Then, turning, she read the face of the man sitting next to her. “Long have you come to us here, Josephus, bringing grain, and long have you been Ardenai Firstlord’s friend. Why did he send you this time?”

“I don’t know, your … Priestessness, Ma’am. I only know that Kehailan did the forehead touching thing with me, and told me the ambassador wanted me here. I have obeyed his wishes.”

“For what reason?”

Josephus looked momentarily taken back. “Am I not being clear? I am kind of nervous, and that makes me rattle on, sometimes. Ardenai, through Kehailan, told me to come and see you.”

Ah’krill nodded. “And this you know because Kehailan retrieved it from your subconscious. But he told you nothing more?”

“Yes, Ma’am, your pries…”

“Ah’krill,” she said with a slight smile. “I am Ah’krill.”

“Yes, Ma’am … Ah’krill. That’s correct, what you said.”

“Captain Josephus, may I assume, since my son has sent you here that this information is for me, also?”

“Well, I thought so, yes. Anyways, that’s why I came on up here before going out to Canyon keep.”

“I understand … your ship is being repaired?”

“Yes, Ma’am … Ah’krill. I no sooner got here than the entire computator system locked me out clean as Monday’s sheets. I can’t go anywheres. But then, Ardenai told me not to, so I guess it’s okay. Probably his idea of making sure I do like I’m told.”

You are quite probably right,” she smiled, and Josephus realized she was a pretty woman, middle-aged, but very attractive. “Do you think I could touch your thoughts?”

“That’s why I’m here,” he said.

“Thank you,” the priestess replied. She turned her chair, took the Captain’s face in her hands, and slowly brought their foreheads together. “Relax,” she said quietly. Josephus began to float. Very real, very near, came Ardenai’s resonant baritone. Thank you, my old friend. You have done well, and my family and I owe you much. Avail yourself of my home, and wait for me. Ah’din, my sister, will see to your comfort.”

Ah’krill released Josephus’s head, and sat back from him. “Well?” he said, almost immediately, “Do I know anything about that clipper in Sector three?” The priestess’s dark green eyes with their tawny flecks, twinkled with amusement, but before she could respond, Josephus went on. “Did you hear that message?”

“I heard the one meant for me,” she smiled, and turned to her advisors. “For now, this moment, we do nothing. Tomorrow, when the Great Council gathers for its morning session, we shall see if Senator Sarkhan is present. If so, I shall be greatly interested in what he has to say. If he is not present, I shall have to hear nothing at all. Hadban, see if we have any craft left, or if my son and his companions have destroyed them all. And tell my grandchild I wish to speak to him at once.”

Kehailan waved the message aside without even hearing it, and continued to study the huge chart on the screen in front of him. “Gentlemen … there’s something wrong here. Look.” A flashing red dot appeared on the chart. “If Ardenai left SeGAS-7 twenty-eight days ago, traveling at anywhere near the maximum speed of that clipper … he wouldn’t be in sector three, he’d be out of sector one by now, and well into Sixth Galactic Alliance space.”

Eletsky watched the dot move off the chart and rubbed fretfully at his balding pate. “Kee,

why…aw, hell, I don’t understand your thinking at all.” And he didn’t. He was beginning to feel like he was embroiled in some kind of elaborate family argument, one of those where if you didn’t know everything about everything and everybody being discussed, you didn’t have a prayer of understanding why it was going on at all, or who stood to win it, or why that was the way it should go.

“There was a beautiful old rifle in my family,” he said, almost to himself. “Brass grip and butt plate. Had some real historical significance. My cousin Connie wanted it, and it had been her dad’s, though he’d given it to one of my uncles … but outside the immediate family, because he’d had a falling out with Connie and her mom … and when my cousin Connie asked for the rifle, this other cousin stepped out of the woodwork and said that it should be his, because such things should stay with the males in the family … and he said she wasn’t really an Eletsky, because she’d changed her name when she got married, I guess, which didn’t make any sense to me.” He exhaled sharply and shook his head. “My point being, I don’t get this, either.”

“It’s simply this,” Kehailan chuckled. “Why did my sire take the clipper if he wasn’t going to utilize it to the fullest? Why did he take something that fast if he did not wish to go that fast, and why was something matching that configuration reported in two different sectors over a two week period, and then not sighted again?”

“He took it because it’s his?” the captain ventured, not at all sure that was what he was supposed to say.

“No.” Kehailan said. “What was done was done with a purpose. Pythos left the clipper on purpose, Marion. My father needed that specific tool. To go where, and why, is the question. And what is it doing in Sector three, when I have every reason to think he was going to Sector two? And why was the craft off-loaded on Corvus from a freighter?”

“One more why, and I’m going to lock you in your quarters and go get roaring drunk,” Eletsky sighed. “Then maybe this will make sense. All right, why was it off-loaded from a freighter? Logically, because it won’t run, or because whomever has it can’t operate it.”

“Why won’t it run?”

“Hell, Kee, I don’t know …” Marion began, and Moonsgold, who was the third party in the discussion, poked Eletsky with one finger and pointed subtly toward the chart with the other. “Winnie, what?”

“Look up, now,” he whispered out of the corner of his mouth. “Now!”

They looked up to see that the chart had turned into the High Priestess of Equus, and she looked none too cordial. Kehailan saluted her by the brushing of his right hand across his left and said, “Ahimsa. Equus honors us with your presence. How may I serve you, Ah’krill?”

“Responding to my message would be an acceptable start.”

“Oh,” he said, rather weakly, “that grandmother. Please forgive me. I do not consider you my … I mean, I thought it was ….” He trailed off with a slight squeak which did not escape her.

“Best not say that, either, whatever it may be,” the woman advised. “Ah’rane and I will be speaking together about you. So, what thinkest thou, child of my child? You have heard?”

“Of course. Captain Eletsky and Doctor Moonsgold and I were just attempting to decipher the hieroglyphics of Ardenai’s … odyssey.” Kehailan squeezed his eyes shut and thumped heavily into a chair. “Someone, one of the principals in this, is either a fabulous logician, or having fabulous luck, and I just can’t figure which it is. Have you any thoughts, my … Ah’krill?”

The woman made a small gesture with her hands and said, “It would please me if you would say it, Kehailan.”

The commander gave her a look that was utterly blank, and Moonsgold leaned in, whispered something, and leaned back. “Have you any thoughts, Grandmother?” He said. It was the right thing. She smiled.

“I have. However, I would like you to tell me everything you know about this, while Captain Eletsky prepares Belesprit for departure. Your current assignment has been … postponed until a later date, and you have been put at my disposal.”

“I see,” Eletsky said coolly. “May I ask where we’re going if not to Anguine Prime?”

“I do apologize for commandeering you,” she smiled, reading his voice and expression. “You are going to Corvus. I want to know what Ardenai Firstlord’s clipper is doing there, and why it came by freighter rather than under its own power. Is it wrecked? Is it damaged? Was it booby trapped like Ah’riodin’s shuttle? Where did it come from? When was it picked up? Where is my son?” Her voice had hardened, and her knuckles were white on the arms of her chair.

“We’ll go,” Eletsky said hastily. “Let me get my navigational people out of this …” he waved away from the main docking ring, “…conference … training thing they’re at today. We can be under way in an hour. I promise. We are a science vessel you know. We do science stuff once in a while.”

Nothing stirs the blood and makes the skin prickle with excitement like the hum and shudder of a great ship getting underway. To see the SGA’s newest science vessel slide by on her way to the space doors, clearance lights flashing, brought a crowd to every observation window on every deck of SeGAS-7. To see her Paracletes flying both the SGA colors and the colors of the Great House of Equus, doubled the crowd and the speculation. Adjutant De Los Angeles nodded and smiled, watching her nearly silent passage. Then he turned away from the window and headed back toward the Judicial Intelligence Wing. He needed to finish unpacking after his vacation, and he had men in lockup who needed to be questioned about what, exactly, had gone on while he was away.

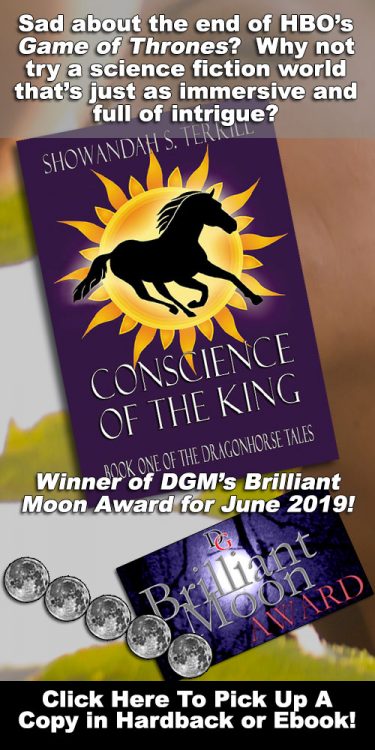

Check back next week for the next chapter in this exciting serial from the Dragonhorse Rising universe. To learn more about Dragonhorse Rising and the world of the Equi, go to: http://www.dragonhorserising.com . You can also follow them on the Dragonhorse Rising Facebook page.